The following appeared in the Albuquerque Journal on July 14, 2022.

Superintendent Scott Elder recently called this the “hardest year we’ve ever been through” due in largely to the need to reduce the number of staffed positions, including teachers, at Albuquerque Public Schools.

Change is hard, especially for large bureaucracies like New Mexico’s largest school district. But change is necessary at APS. That’s not just the Rio Grande Foundation’s view; it is the conclusion of the Legislative Finance Committee’s recent report on APS, which shows a district awash in money but bleeding students.

Many families, like my own, have left APS. Many families felt betrayed by Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham’s COVID school closings, which cost students a year of classroom time and a great deal of academic and social progress. The governor’s decision to shutter the schools will have lasting, negative impacts on our children that are only now starting to be accounted for. Many families with the resources to do so left the district or even the state. Many aren’t coming back.

To maximize the beneficial use of the district’s resources, the LFC recommends “right-sizing” the district’s “footprint,” including eliminating teaching and other positions as well as reducing the number of facilities including school buildings to reflect a shrinking student population. This trend began before COVID but has accelerated since.

The LFC’s numerous other recommendations need to be implemented. I do believe the current school board wants to allocate resources in ways that make sense for the district and its 71,000 students.

But the APS Board of Education doesn’t fully control the district’s budget; the Legislature and governor do. And, with money flowing into the state at unprecedented levels, the political incentives in Santa Fe are aligned to pour more money into the system. When money is plentiful, politicians are loath to make difficult and often unpopular decisions to redeploy resources. Sadly, the LFC can write reports, but until politicians in Santa Fe act, things won’t improve.

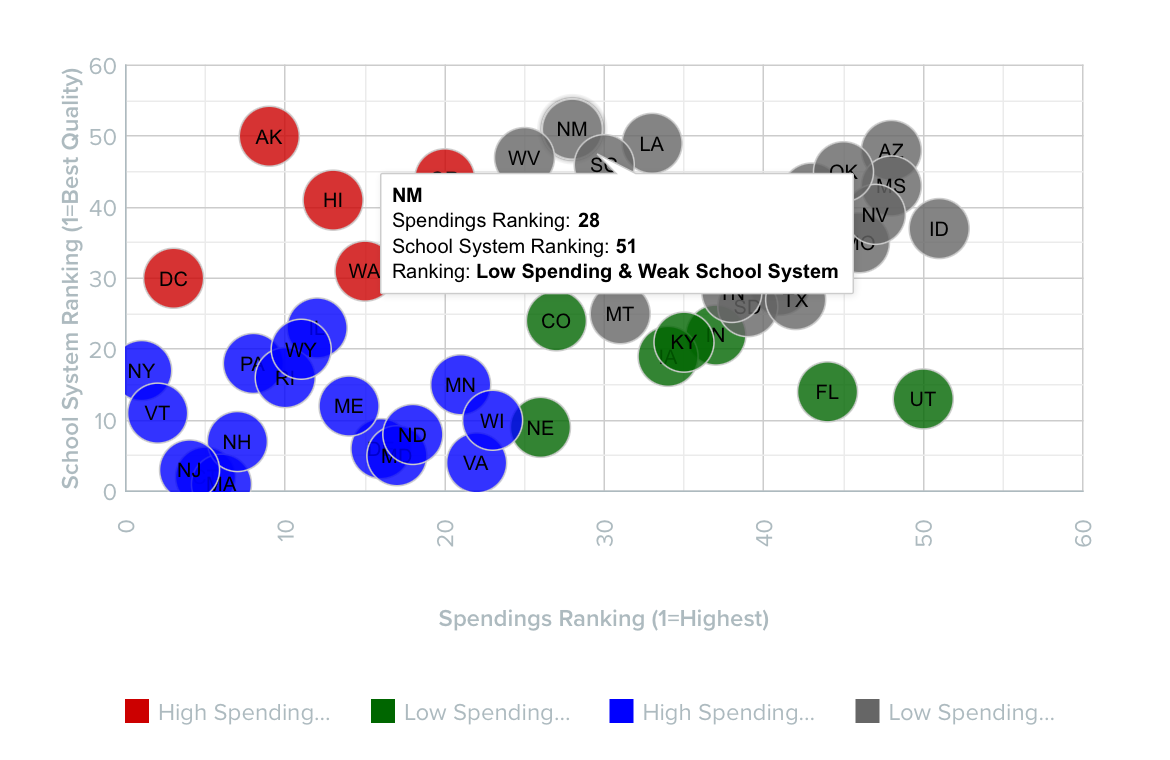

It is time to put to bed the myth of “underfunded” local schools. With the recent adoption of the district’s $1.93 billion budget divided over 71,000 students, APS will be set to spend a whopping $27,000 per student in fiscal 2023.

In addition to “right-sizing,” APS needs to implement innovative approaches to simultaneously improving educational outcomes. Alas, this governor and Legislature have chosen to keep power and money centralized in Santa Fe rather than fully empowering local leaders or, heaven forbid, parents, to decide what makes the most sense for themselves and their families.

While the local school board has limited power over serious reforms, they can be advocates for charter schools and work to expand that important form of school choice. Expanding intra-district choice is an additional way to expand educational freedom.

But real education reform in New Mexico must come from the top. Republican gubernatorial candidate Mark Ronchetti has stated clearly that he wants to bring school choice to our state by having money follow the students. Poll after poll shows Americans agree with him, a trend that also has accelerated since COVID. Parents and families should be able to use their education funds to pursue options that work for them, not the bureaucrats in Santa Fe.

Change won’t happen overnight. As a starting point we need a governor who will stand up to those who want to keep the failed status quo and just spend more money. Even a reform-minded governor can’t do it alone as real school choice needs buy-in from the Legislature. So, right-sizing and reforming APS – including but by no means limited to school choice – will requires cooperation and buy-in from many different groups of elected officials. We have a lot of work to do for our children, but now is the time to begin.

Paul Gessing is president of New Mexico’s Rio Grande Foundation. The Rio Grande Foundation is an independent, nonpartisan, tax-exempt research and educational organization dedicated to promoting prosperity for New Mexico based on principles of limited government, economic freedom and individual responsibility